Finding inspiration through an open approach to employing traditional printmaking techniques

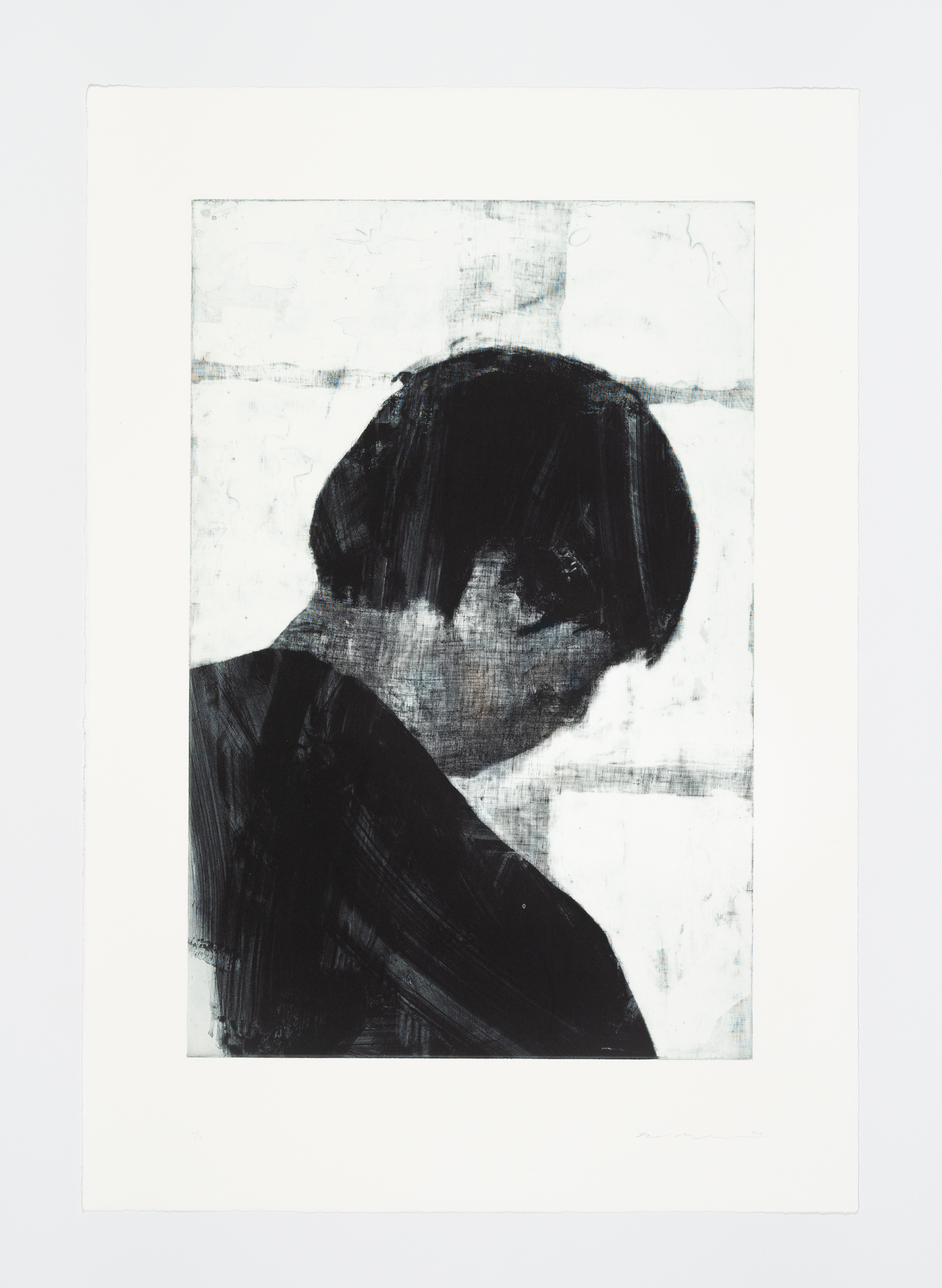

Matt Saunders | Technique, improvisation and invention

Inquire

Matt Saunders paid his first visit to Niels in 2014. In the years since, printmaking has joined film and photography as a central paradigm in both the things he makes and the way he thinks about images.

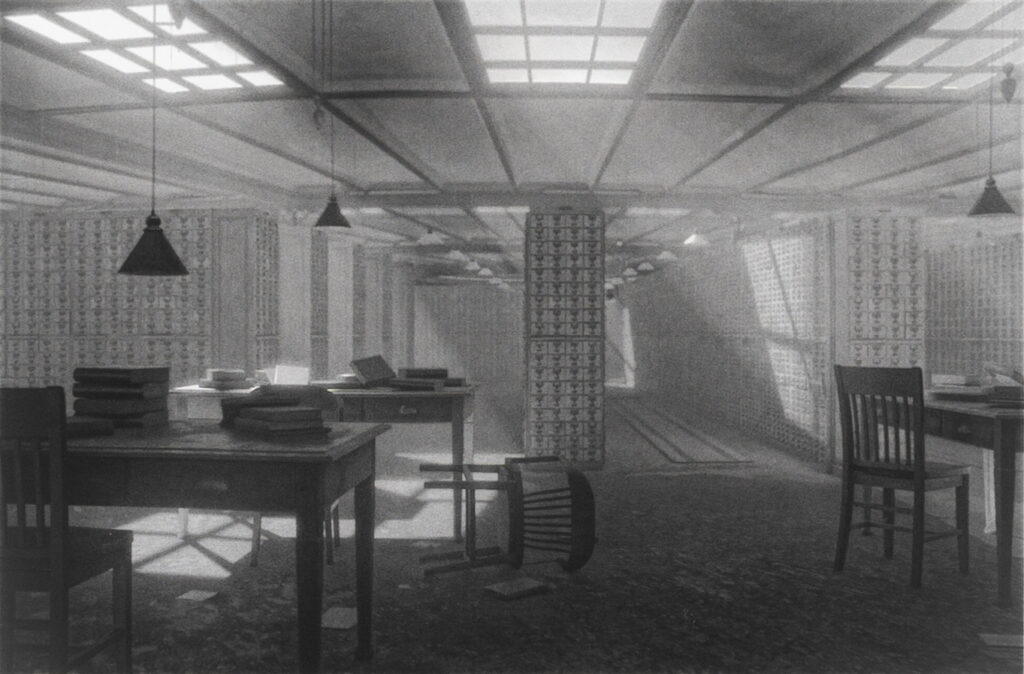

The first thing that hits you about the printshop is the smell. Dank, oily, rosinous, with a whiff of industrial hand soap, it fills the entrance hall. The walls of this improbably long corridor flutter with hundreds if not thousands of paper scraps, invitation cards mostly, with a few proofs, a few clippings, a few notes tacked up once and left to accumulate—an underbrush of ephemera that catches and keeps the scent of innumerable ink-ups and wash-ups, so that now it overwhelms your senses. The entry is a tunnel through time. This was the atmosphere that greeted and emboldened me in the first and best deal I ever reached with Niels Borch Jensen: we agreed on day one that the best plan was to throw out the plan.

The printshop has become a studio away from the studio—a place I go when I really need to crack open my thinking

Matt Saunders

I’ve never asked Niels exactly what he imagined we’d work on when he first invited me to visit him on Prags Boulevard. I must have been afraid of the answer, for at that time I (wrongly) thought of the printshop chiefly as a mecca for polymer photogravure, whereas my curiosity about print, fostered through deep immersion as a student working on metal plates, was messy and handmade, trial and error. Since I was mostly exhibiting photographs then (albeit messy, handmade, trial and error photos), my fear was that he’d want a streamlined, economical setup in which I’d give him a picture and he’d print it.

So, I remember nervously trailing Niels down that corridor past the bathrooms (they were missing a seat on the toilet back then) and the kitchen. Then, salvation! Following my nose, I dashed into the sink room, where I spied russet-stained walls and a cracked, congealed, impossibly large tray of dried-up acid. Later, Niels opened the door across the hall to a plume of powder, revealing a singed gridiron and an aquatint box the size of a New York City bedroom, set up to tumble on a motorized axle. “How big can you aquatint?” I asked. (Four by-eight-feet-ish, it turns out). “Copper!” we said to each other. And we were off.

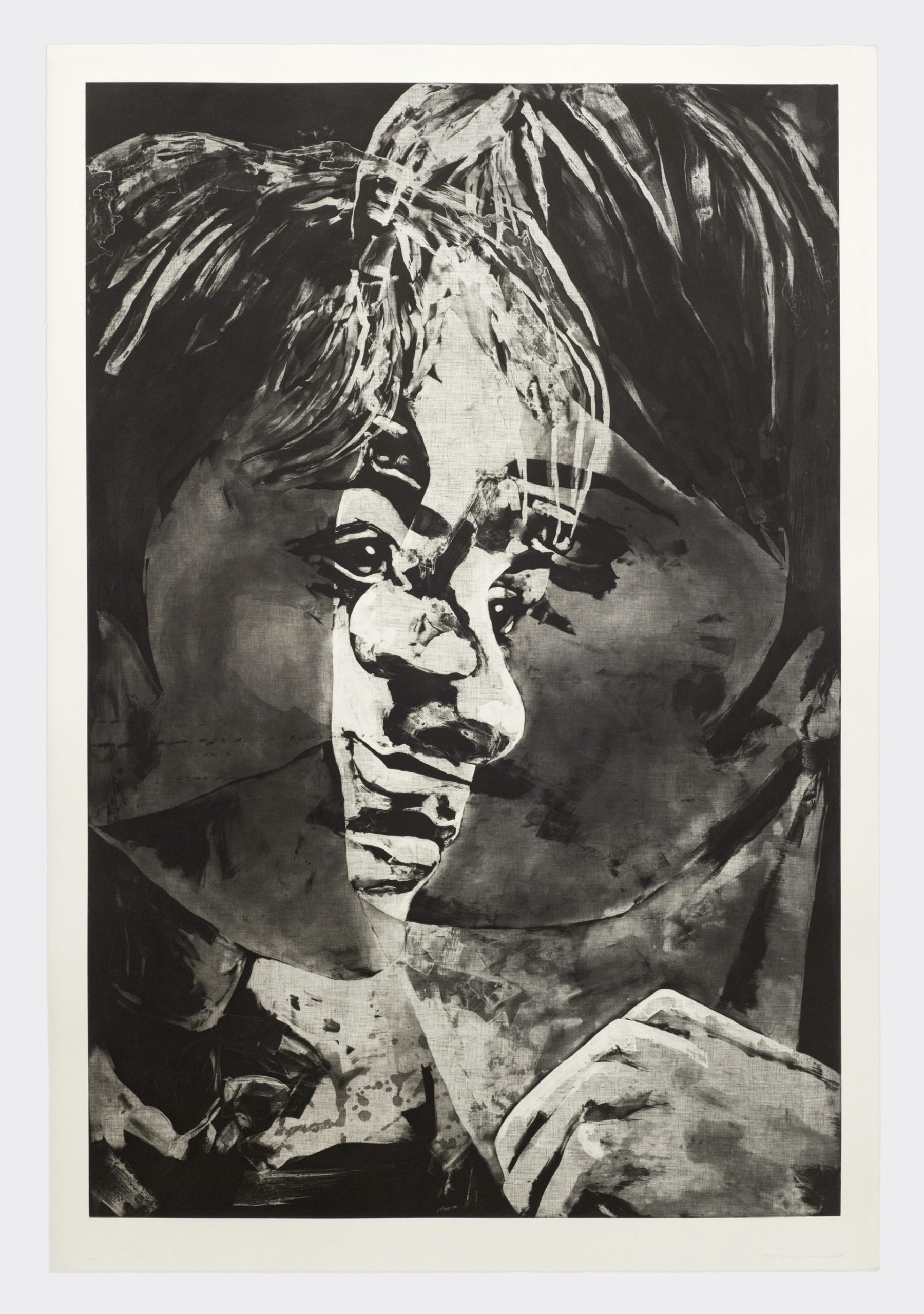

I’ve clearly romanticized that moment, but I’m blinded by the relief I felt that Niels was willing to start something open-ended with me, not just plan something tidy. I felt his relief too, and his excitement to dust off the old techniques. Yet, if I came in with enthusiasm to learn from Niels’s depth of technical know-how, I quickly realized his real brilliance— what makes working at the printshop such a productive pleasure—is his appetite for not-knowing, his capacity to improvise, experiment and play. This is how he got so famous for photogravure: working doggedly to figure out what polymer plates could do. I believe my time working with Niels has overlapped with his renewed use of older forms—intaglio, then woodcut, then monotype—returning to them with fresh eyes, if calloused hands.

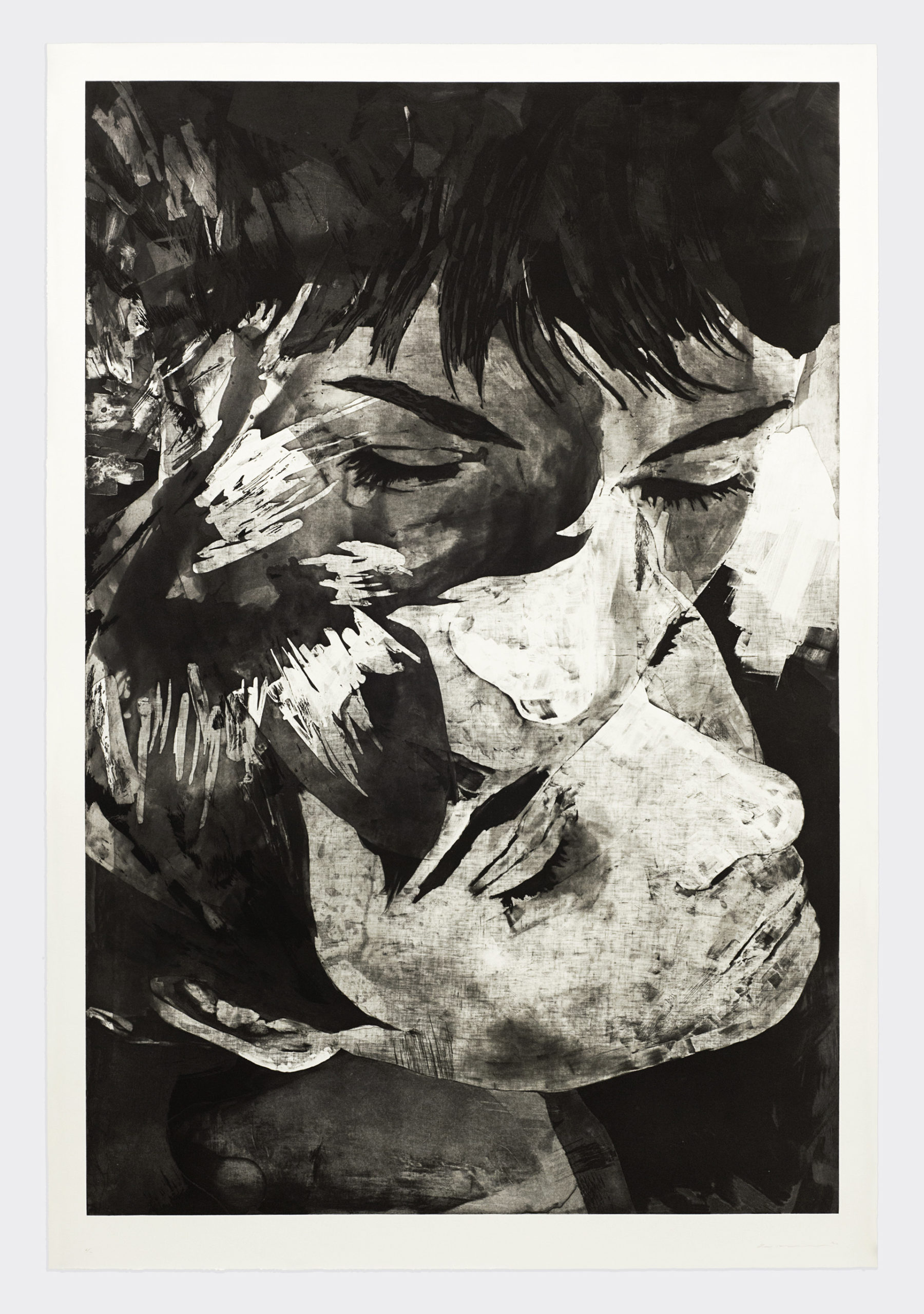

Myself, I’m happier with a brush than a stylus. I paint wet into wet and like to think of painting as a time-based medium. I often use analogue photographic materials in order to handle directly that moment of becoming, the space of time in which a work appears.

Niels and I discussed how the acid bath was a kind of developer, and we turned to soap ground as a way to crack open the drawing, to let it change and stay active as the plate was biting. Something I’d heard of but never tried, soap ground involves mixing soap with an oil so that you get a resist that is somewhat soluble in the acid. It slowly breaks down and so is traditionally used for planned imperfection—mottled and random effects. I wanted to deploy it as a time release: The thicker or thinner the ground, the longer or shorter it would resist the action of the acid. I wanted to be able to make a single pass on the plate that could achieve a full range of grays in one bite, but also stay treacherous, somewhat beyond control. We tried all kinds of mixtures, with different soaps and different fats, from fine linseed oil to butter from the kitchen. I learned how to lay down thick or thin in one go, and how to layer gently on the polished plate. When we got too controlled, we found ways to “break” it. (“Breaking the image” or “breaking the plate” are the phrases Niels and I use most frequently in the shop.) I found that splashing acid on the soap ground quickly cured it, made it slower to wash off, so soon I was working back and forth between drawing with soap, drawing with acid, blasting with water, drawing again. The loop between drawing an image, fixing that image and the acid bath itself became one organic rhythm—not so much working on a plate as working with it.

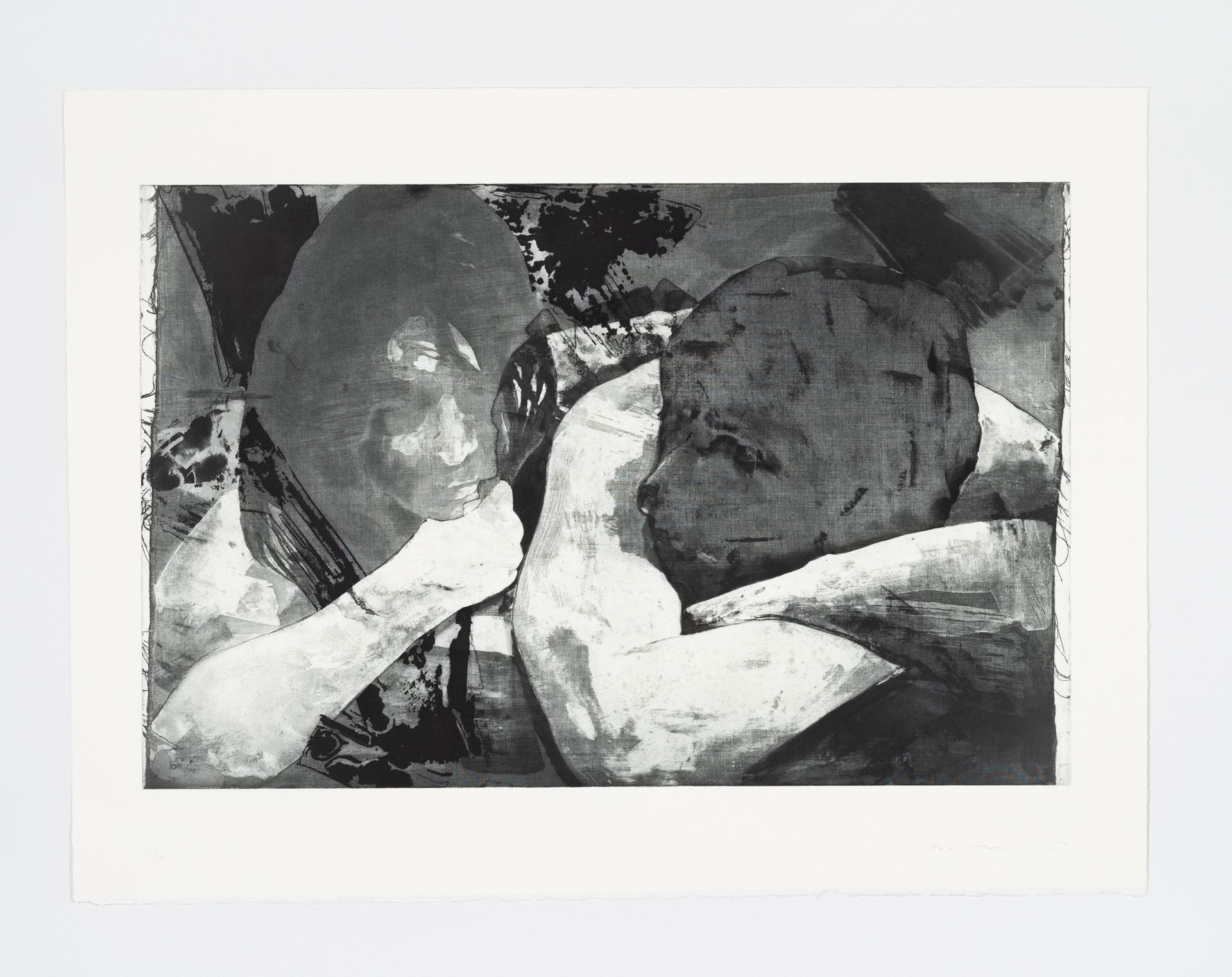

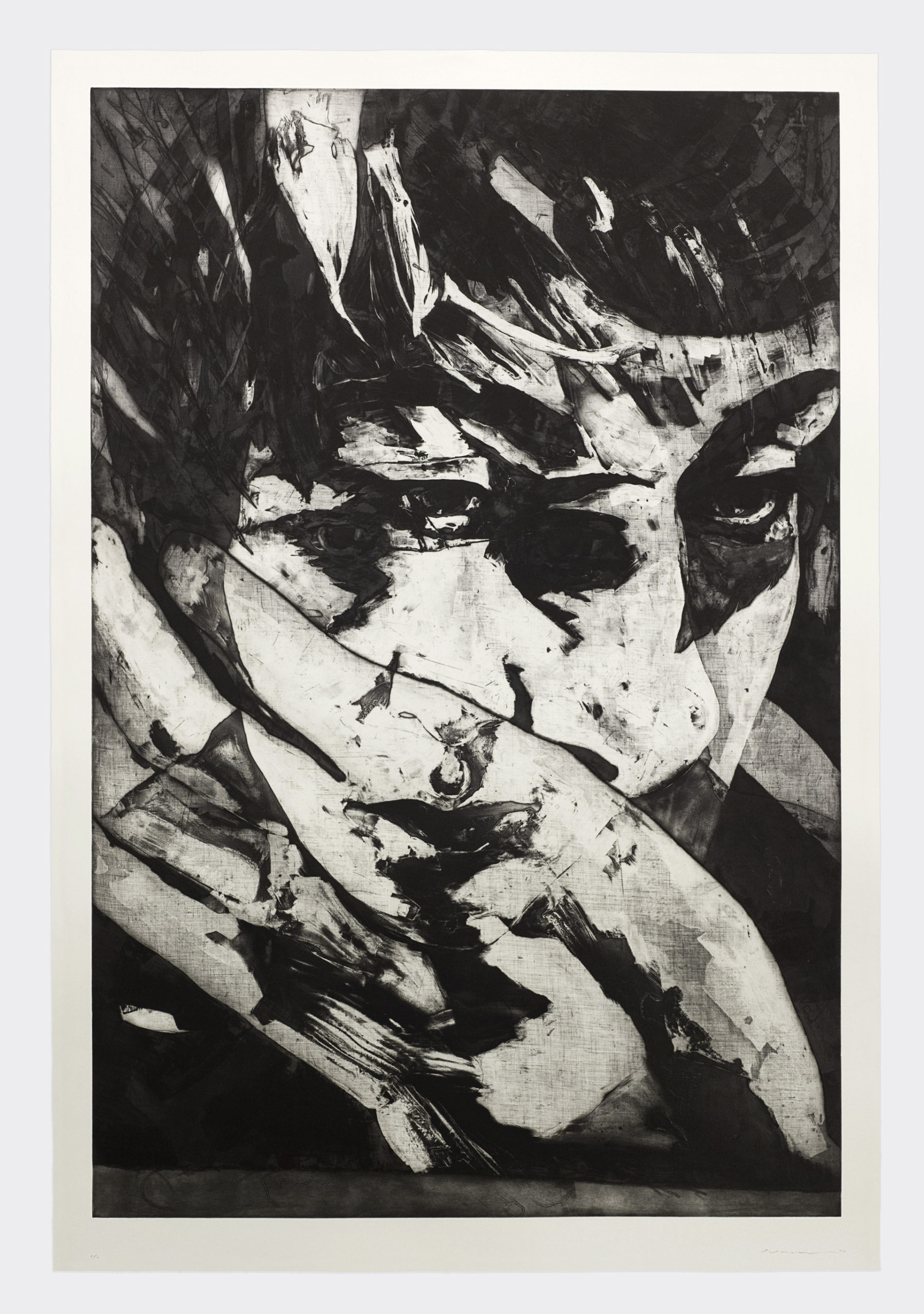

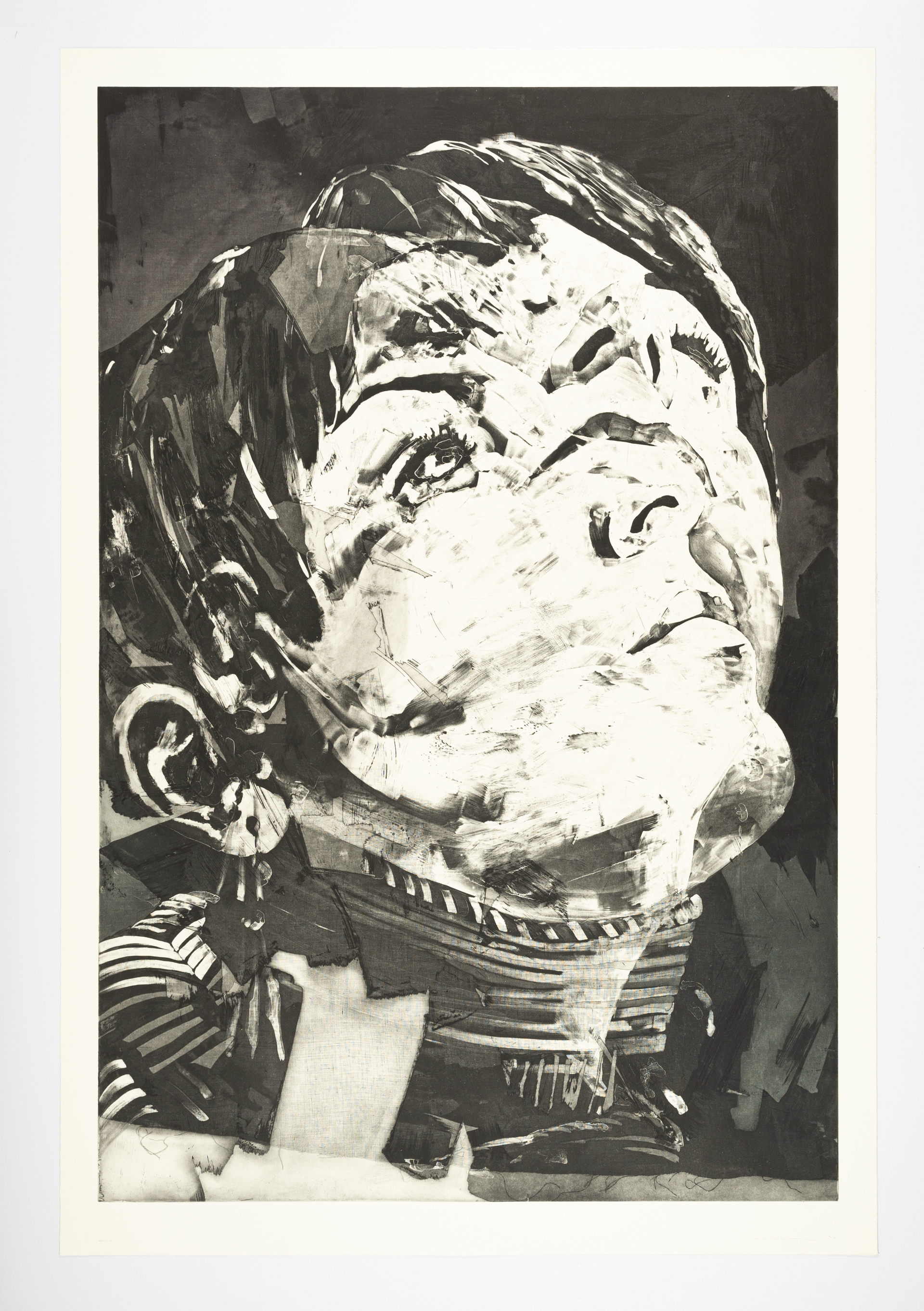

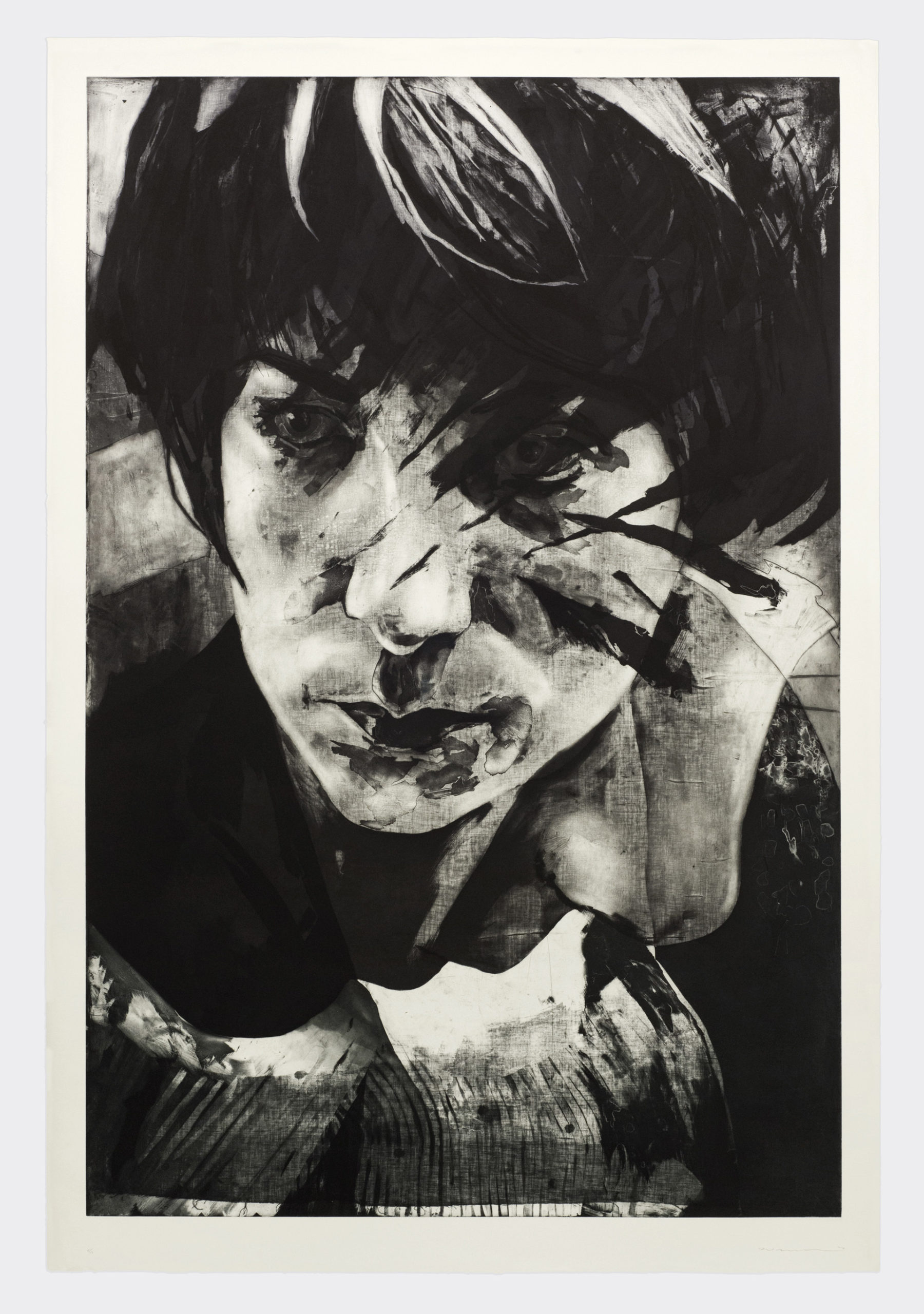

The biggest project we made in this way, Ratlos / Indomitable, tried to bind the image and the process and materials more tightly than ever. The images on the plate, overlapping double portraits of a character from the films of Alexander Kluge, were built from one soap ground drawing atop another—they pulled and dissolved and interfered with each other in a kind of unpredictable, hand-drawn double exposure. We used soft ground to imprint the weaves of fine linen for a tonal structure that differed from aquatint.

The copper we cut was the largest size I could lug around by myself. Squatting on top of the plates to draw, dragging them to and from the sinks, I etched a kind of subconscious story onto their backs through the heavy wear, tear and travails of their shop life. For exhibitions at the Saint Louis Art Museum and Marian Goodman Gallery in London, I installed prints made from the backs of these plates along with those made from the fronts in the same room as videos on translucent, double-sided screens, because in the sheer heft and physicality of the copper I found the impulse to undo its opacity, to render it, and the process, transparent. Such complexes of meaning and making come about through the openness and experimentation Niels fosters. We’ve overexposed polymer plates on purpose (they get too dark), then used polyurethane floor varnish to draw back into them (closing in the holes). We’ve soaked watercolors into linen in order to draw it out, both sides at once, through monotyping.

Printmaking has been transformative for me in the past several years, not only because of the results, but because the printshop has become a studio away from the studio—a place I go when I really need to crack open my thinking. All great printers have the tinkerer’s mastery of technique, improvisation and invention, but Niels is particularly good at abandoning the plan to invent the way. It’s changed my work. And I’m so glad they put a seat on that toilet, a new shower and a better bed in the guest room. Whenever they let me, I’ll come to stay.

Matt Saunders 2021

About Matt Saunders

Matt Saunders’ work challenges the boundaries of artistic media. He enacts painting as a time-based and transitive medium through his camera-less photography, multi-screen animation and innovative painting and printmaking processes. Best known for his haunting portraits and landscapes (the imagery culled from a myriad of sources including avant-garde cinema and found photographs) and moving-image works, Saunders’ practice uses analogue materials to explore the fleetingness, mobility and affective power of images.

Matt Saunders’ work has been in numerous group exhibitions including at: Ecole des Beaux arts de Paris, France (2022); American Academy of Arts & Letters, New York (2022); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2020); Mass MoCA, North Adams, Massachusetts (2017); The Photographer’s Gallery, London (2016); Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2016); the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2013); de Cordova Museum, Lincoln, Massachusetts (2012); the 2011 Sharjah Biennal; and the Apsen Art Museum, Colorado (2011). His work is in the collections of major institutions including The Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Guggenheim Museum, New York; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, California; the UCLA Hammer Museum, California; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C. Saunders was the 2015 recipient of the Rappaport Prize from the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, the 2013 Prix Jean-François Prat and the 2009 Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation award.

Matt Saunders was born in 1975 in Tacoma, Washington. He lives between Berlin, Germany, New York and Boston, Massachusetts where he currently teaches at Harvard University. He has been collaborating with BORCH Editions since 2014.

Learn more about Matt Saunders