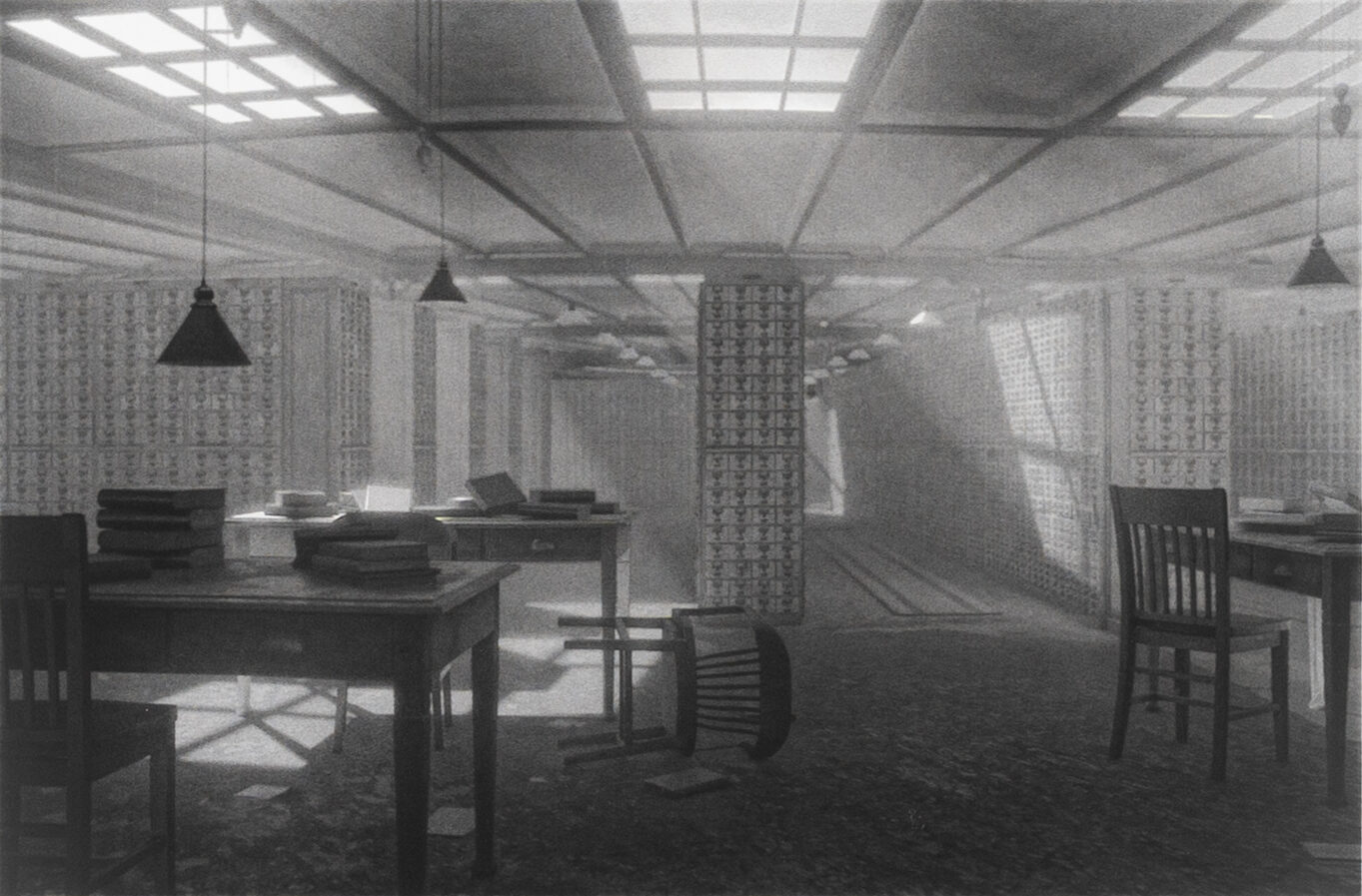

A strange glow pervades a collection of endless archival drawers.

Fiona Tan | Shadow Archive

Inquire

1 Otlet and La Fontaine’s UDC was an adaptation of the

Dewey Decimal System.

2 The British Museum, itself an attempt at encyclopedic

representation of knowledge, bought a set of the Shadow

Archive photogravures, which now reside just metres

from the old Reading Room, which is nicely apt.

3 Archive, (2019) 5’45” loop

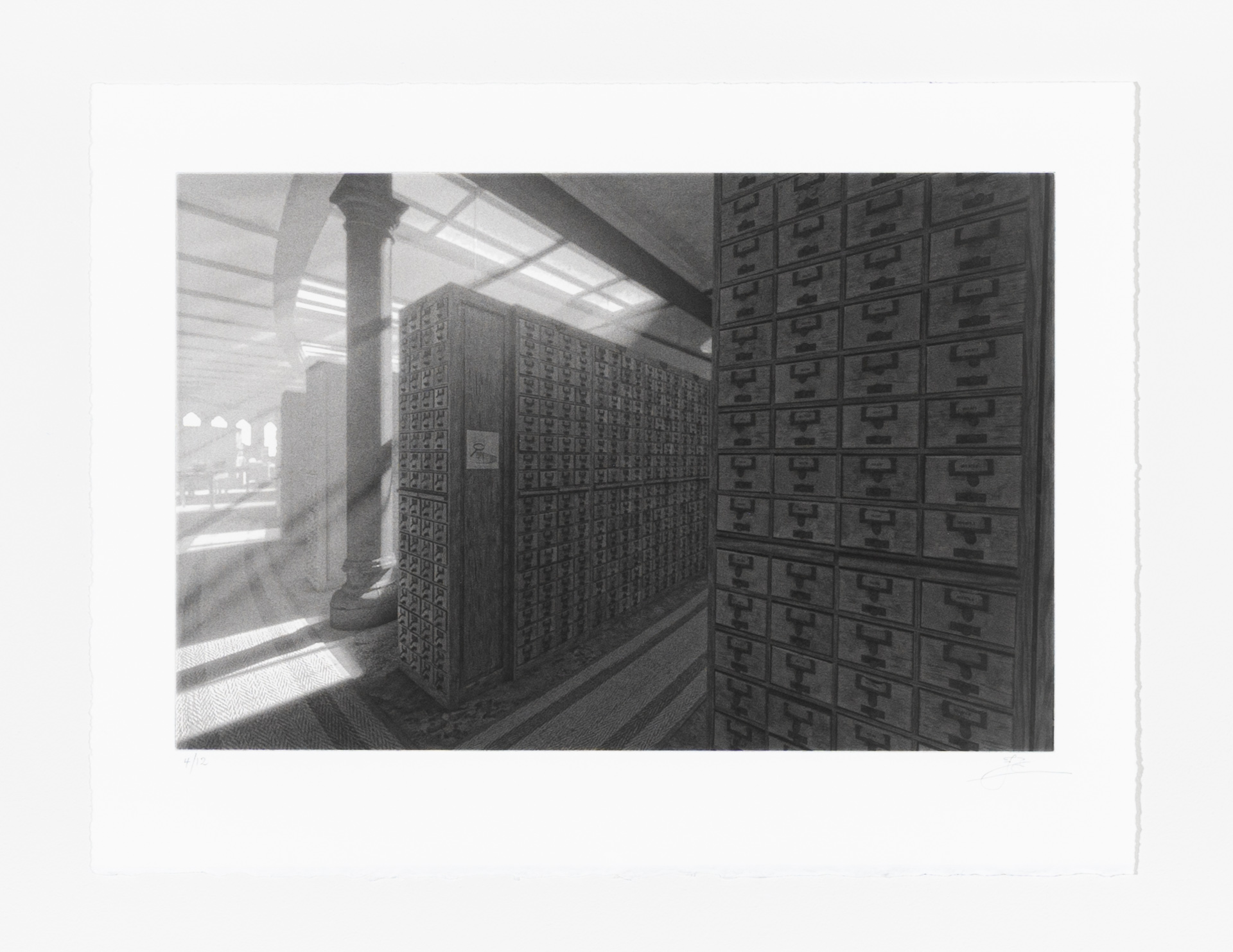

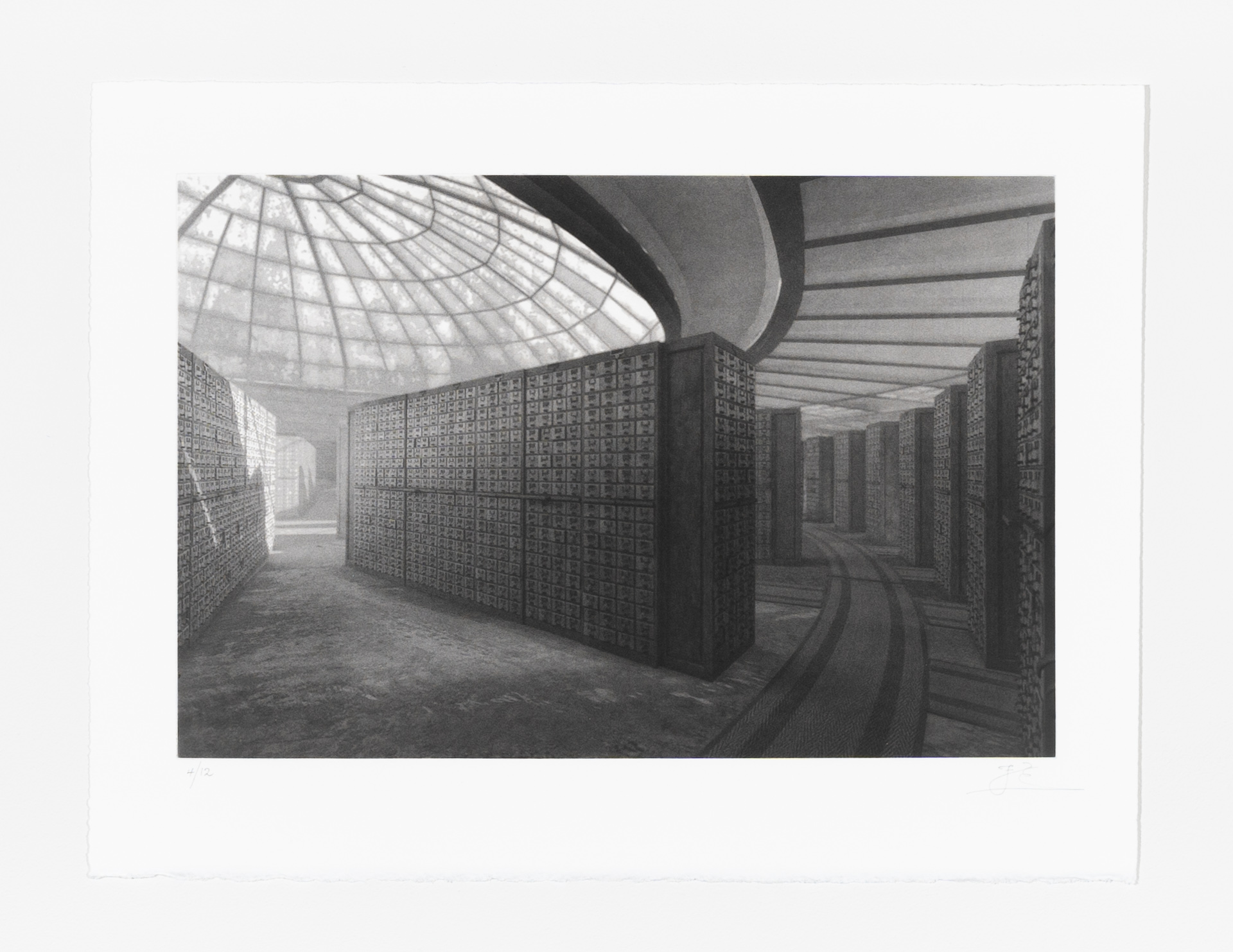

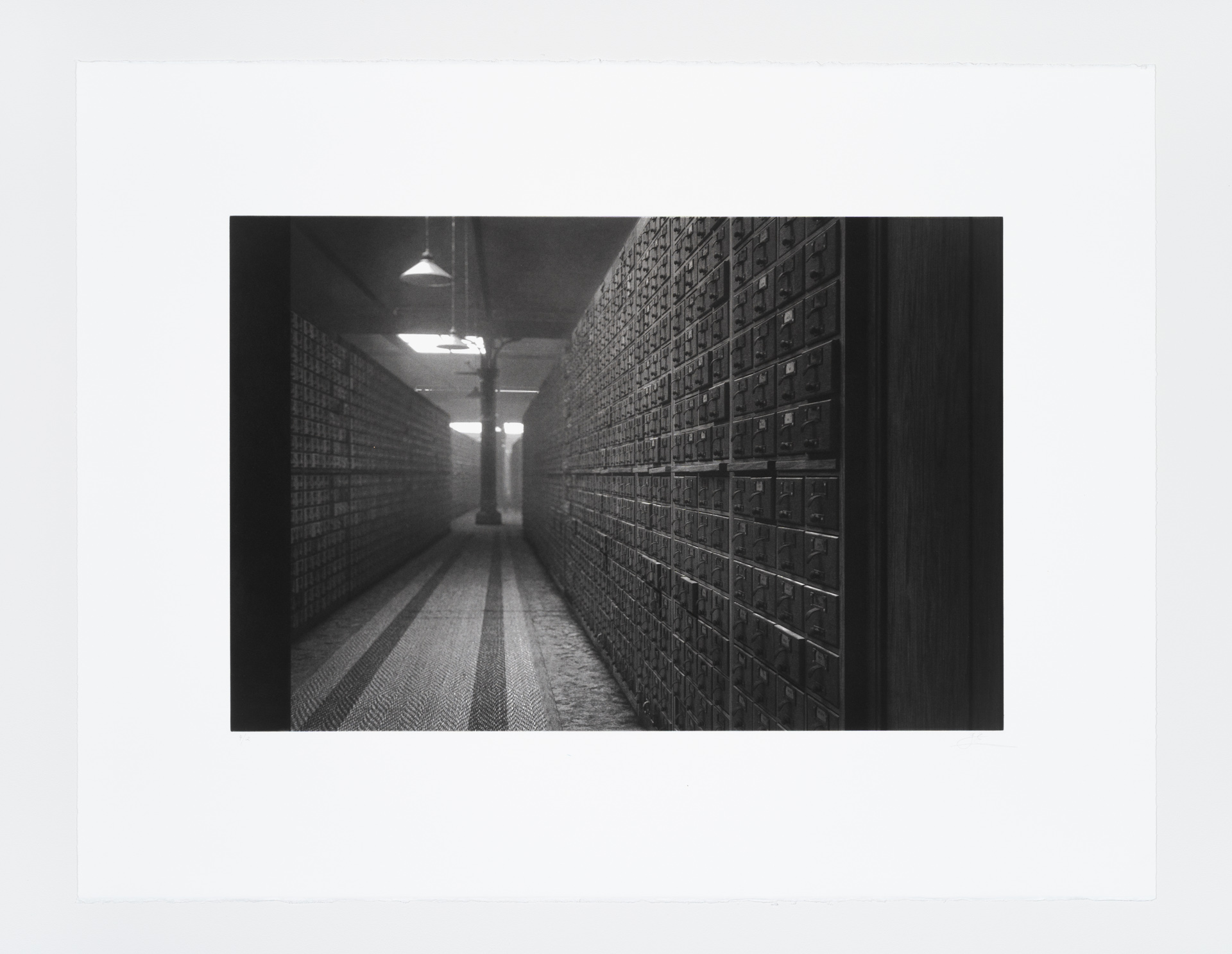

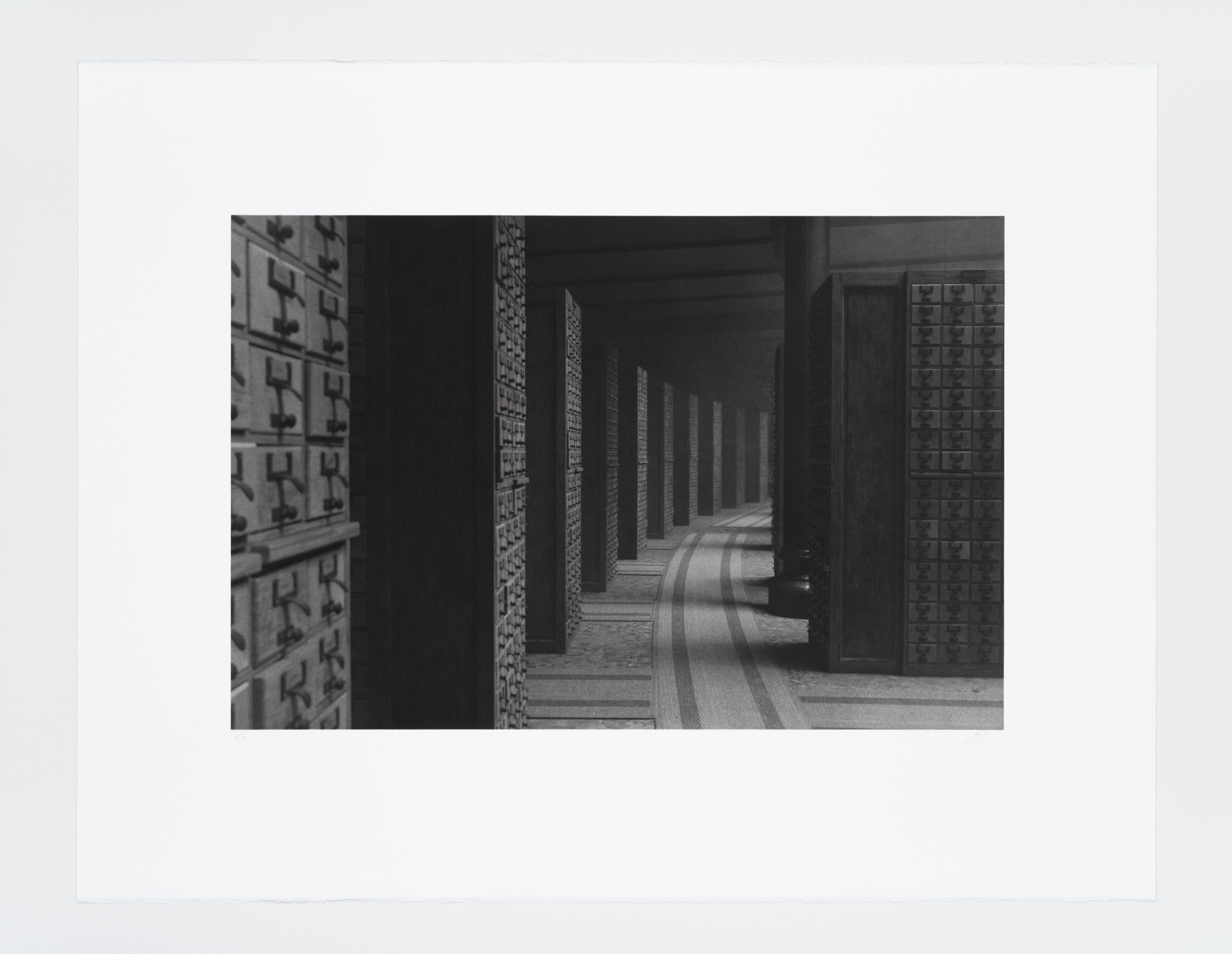

Fiona Tan’s Shadow Archive (2019) is a vision of a vision, a detailed portrait of a fictional building for the real “Mundaneum,” which was established in 1895 as the ultimate depository of all human knowledge. The brainchild of Belgian pacifist Paul Otlet, who devoted forty years of his life to it, the Mundaneum was both madly utopic (he conceived it as a stepping stone to world peace) and sensibly concrete. The information was written on cards; the cards were filed in drawers, and the drawers were arranged wooden cases. To keep track of it all—some sixteen million cards—Otlet and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Henri La Fontaine developed the Universal Decimal Classification system, still in use by many libraries.1 Time and two world wars, however, took their toll on the material substance of Otlet’s dream. The remnants are now held in Mons, Belgium, where Tan spent two years conducting research for her 2019 exhibition L’Archive des Ombres / Shadow Archive at the nearby Musée des Arts Contemporains, Grand-Hornu.

Today, Otlet’s legacy can be seen in two places: the “heaps and heaps and heaps of pieces of paper, rotting away” in Mons, and the existence of Wikipedia (an admirer of technology, he also conceived a “Mondothèque” desk that would share information electronically). Seeking to bridge these two domains—the corporeal and the digital— Tan decided to design and build an ideal virtual building for the Mundaneum’s contents. Circular and vast (120 metres in diameter), with card cabinets arranged in radiating spokes, the space may suggest the old British Library Reading Room (a picture of which she kept posted to the wall in her studio),2 Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, or the Circular Ruins of Jorge Luis Borges, or indeed his Library of Babel. Otlet had himself diagrammed his archive as a circle of knowledge, taking literally the “cycle” within “encyclopedia.”

Tan constructed the building in CGI software so she could move through it at will, as in a video game. A looping animation in the exhibition did exactly that, roaming endless corridors of cabinets modelled on the surviving ones in Mons.3 “I wanted it to feel old,” she explains, “like something forgotten that had been rediscovered”—gray light filters through the cracked skylights, drawers stand open, a toppled chair suggests abrupt abandonment. But she also wanted to give the building a form more palpable than digital animation: “I was very deliberately messing around with the borders between digital and analog, between something you can feel and touch, and something that doesn’t actually exist.” Photogravure, with its haptic presence and aura of antiquarian authority, was the obvious choice.

I was blown away by the love, the dedication and the tireless enthusiasm, not only from Niels but from his staff. I took photographs of the tarlatan cloths they use to wipe the plates; they get used and reused so every single inch has at all these colours. I felt like a child in a sweet shop

Fiona Tan

Tan had first heard about Niels from Tacita Dean, when they bumped into each other at Kastrup Airport in Copenhagen. Some years later, curious about how prints might intersect with her film, photography, and installation projects, she paid a visit.

Her first project at the printshop, Studies for Elsewhere I–IV (2018) threaded Thomas More’s 1516 Utopia through 2018 Los Angeles. In Shadow Archives, Tan again sought to wed kindred endeavors and locations separated by time, using a historical intaglio technique to conjure a digital building with precision and material force.

Echoing Otlet’s obsessive pursuit of completeness, she built her CGI edifice at 1:1 scale. As a result, the rendered images have the particularity of film rather than the compressed smoothness of digital. Having designed the spaces, she found it was “really fun to walk around in them, so to speak, and choose vantage points to make the prints from.” We see the vast banks of drawers, some seemingly too high to reach; we see distant sunlight beaming in from the central oculus, and the silhouettes of trees behind; we see the kinks in the carpet, a table piled with books and loose papers.

What cannot be seen is what any of those drawers or books contain. For all their wood and paper hominess, these are data storage containers as mute and withholding as those in a server farm. The soft blacks and velvet grays of the gravures are lovely and also, Tan observes, “kind of stum. You’ve just got these dark, forgotten spaces that are sort of intriguing—telling you a lot but also giving nothing away.”

The beauty is sepulchral. In the end, Otlet’s “puzzling and charming and fascinating” project failed, not just because his sixteen-million cards did nothing to prevent people from killing each other, but because of the founding flaw at its benevolent heart: the casting of knowledge as a fixed, rather than a fluid, thing.

“What motivated Otlet every morning when he got up, I think, was this idea that when I’ve finished, there will be world peace. Dead cert. He wasn’t a doubter. It’s terribly utopian, but in such a rigid way. You can’t fly with it. You can’t dance. He didn’t have any humour. It’s a real paradox.”

Susan Tallman

No Plan at All, Hatje Cantz 2021

About Fiona Tan

Fiona Tan’s work encompasses photography, printmaking, film and video installation, and she has written and directed two feature length films. Her research-based practice explores themes of identity, memory and history, often utilising image archives and museum collections .

Fiona Tan has exhibited widely over the past twenty-five years and her work is part of many international private and museum collections. Solo exhibitions include at the Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam; Museum der Moderne, Salzburg; Museum Ludwig, Cologne; Musée des arts contemporains Grand Hornu; The Baltic, Gateshead; National Museum of Art, Osaka; and MAXXI, Rome. In 2009 Tan represented the Netherlands at the Venice Biennale with her solo presentation Disorient. Her work is held in the collections such as the Centre Pompidou, Paris; Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin; New Museum for Contemporary Art, New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; and Tate Modern, London.

Fiona Tan was born in 1966 in Pekan Baru, Indonesia and grew up in Australia before relocating in the late 1980s to Amsterdam, where she continues to live and work. She has been collaborating with BORCH Editions since 2018.

Learn more about Fiona Tan