1 Including Greg Burnet in New York, Crown Point Press

in San Francisco, and Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles.

Like a carillon, the title of Julie Mehretu’s luminous 2020 etching quartet rings bells in quick succession. Joan Didion used “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” to headline her famous article about aimless hippiedom in the Summer of Love, and also for a subsequent book of collected essays, reread by Mehretu in the Summer of COVID. Didion had herself filched the phrase from the last line of William Butler Yeats’s The Second Coming, written amid the political mayhem and global pandemic of 1918–19, a poem whose opening stanza has provided epigrams of societal devolution for a century:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world

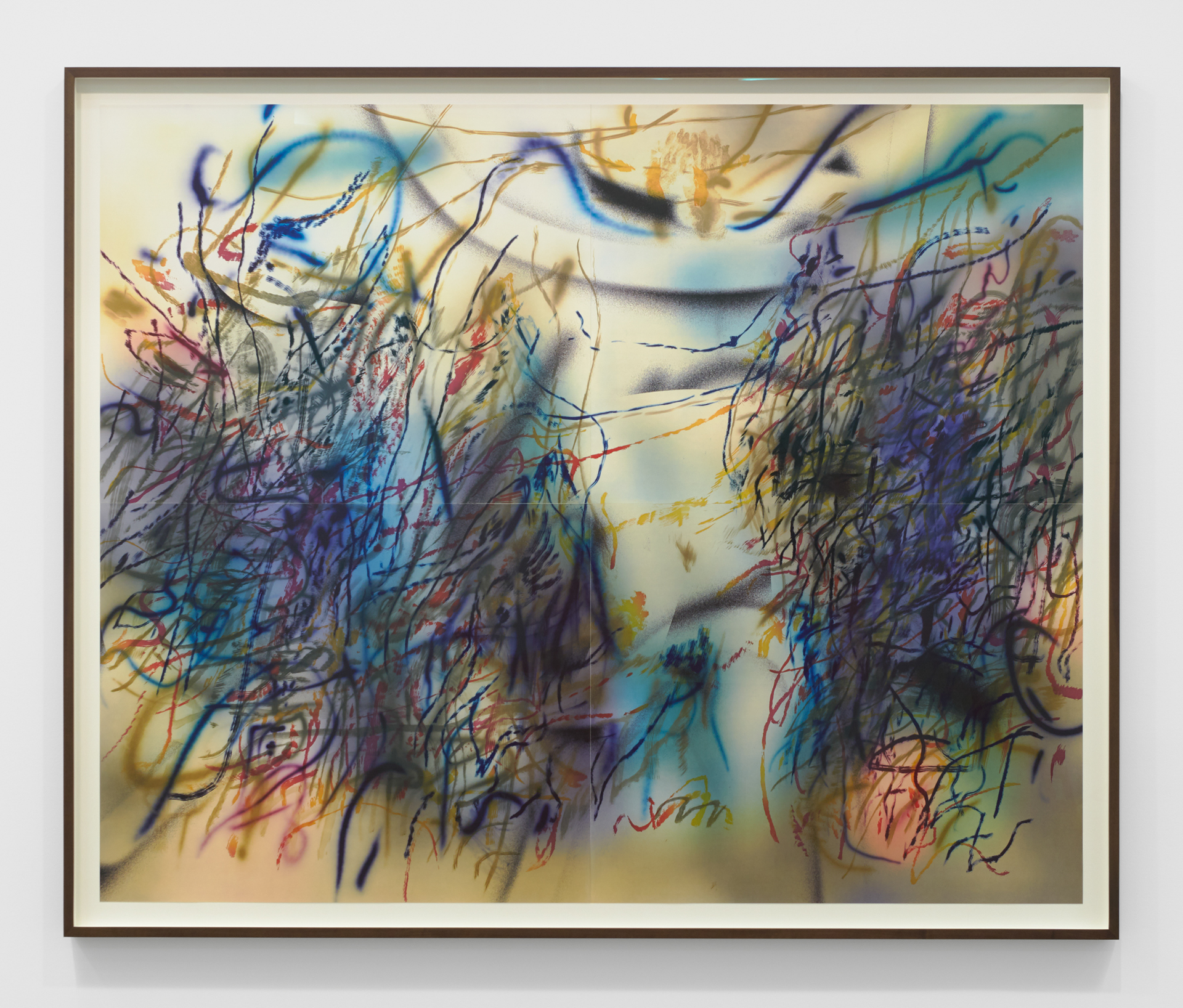

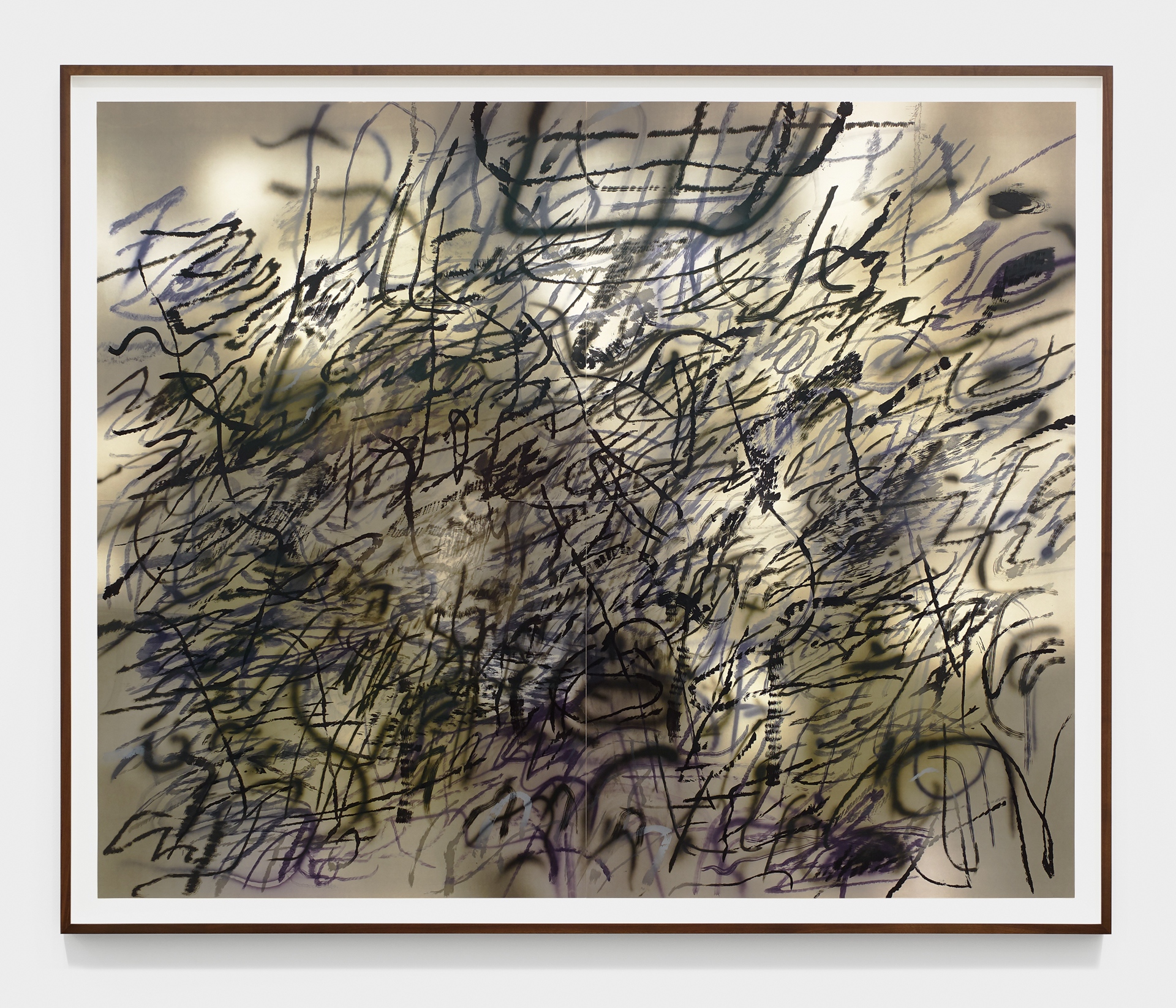

The metaphor matches the flurried energy of Mehretu’s prints—the widening gyre, the sense of things loosed—but for one critical difference: “mere anarchy” has no purchase here.

Like many artists who take to print, Mehretu understands images not as integral wholes but as accretions of parts. In painting as well as prints, she builds compositions in layers that interact without merging, like friends waving to each other on either side of a window. She often works in series, using adjacency and sequence to extend threads of kinship and difference. She likes systems that exist at the frontier where complexity may be mistaken for chaos weather, urban sprawl, revolution. Prints have figured prominently in her career, and when she took up residence in Berlin, Niels was eager to find a joint project. It was a challenge. Mehretu was already working with eminent printshops in the United States and had no desire to repeat herself.1

The most compelling and important thing in working with prints is that, in my practice, you’re able to take things apart and look at things in their various parts and put things back together in a way that you can’t do in painting or drawing.

Julie Mehretu

“One day, Niels came by and was talking about photogravure. I didn’t really understand the process, but I’d seen what he’d done with Tacita [Dean] — these incredible, momentous pieces. In my studio at the time, there was a big unfinished painting—just white ground with a drawing of architecture in Damascus. We’d been working on it for at least a year, but I was now on the cusp of something else, starting to draw more loosely and working with blurred photographs. Some of those newer things were also up on the wall. I asked Niels if he could take a photo of the Damascus painting and show just the architectural drawing. He said he could, and also that he could layer it with a blurred photograph in one photogravure plate. He said, we can do that in Photoshop and send it to you with transparent mylars so you can draw over it, and then we can make one photogravure plate of all of that, and then you can come in and work into copper. I kind of understood what he was talking about, and it seemed exciting.”

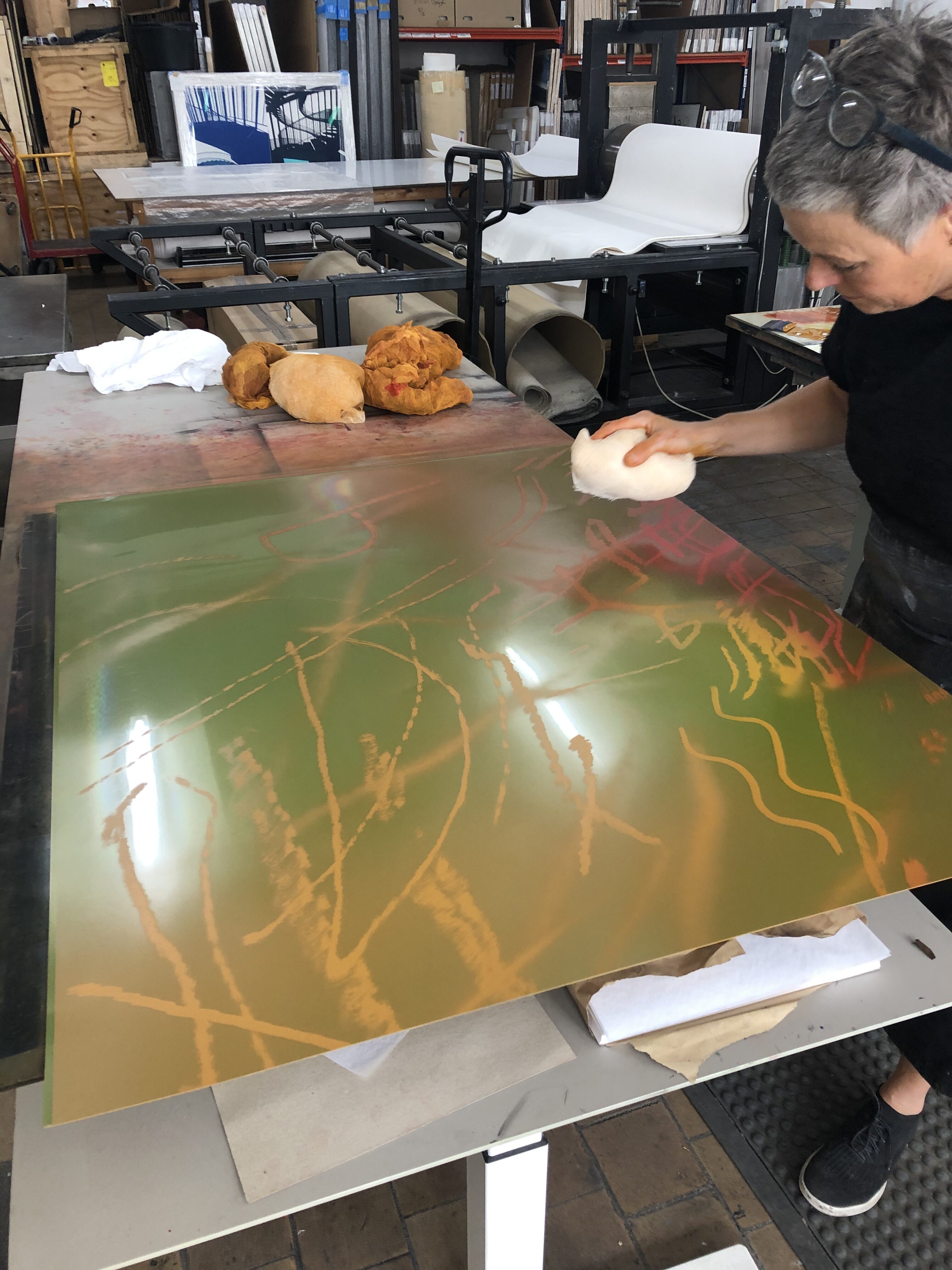

To approximate the panoramic scale of the painting, the image was divided into six panels and inkjet-printed on six large sheets of paper. In her studio, Mehretu drew on mylars laid over the proofs; the mylars were then sent to Copenhagen, where they were scanned and combined with the architectural drawing and the blur to make twelve photogravure plates. When she got to Copenhagen, the completed proofs—incorporating architecture, blur and drawing—were up on the wall: six panels, more than two metres high and almost six metres long. It was impressive but, Niels observed, “not fully alive.” He suggested another layer, drawn with sugar lift on copper.

“I worked on the copper on the floor (they gave me things to cover my feet so I could walk on the plates) and the gravure image was in front of me on the wall. I had to work backwards, since the left side of the image on the wall would eventually be combined with the right of the plate I was working on. I guess they just had faith that I would figure it out. And in the end, something about working blind while being bodily informed manifested itself on the plate. Copper can do things the flatter polymer plates can’t. A copper plate is like a thin sculpture with a miniscule landscape, a surface with its own geography. When we printed them, we shifted the blacks in different marks—green black, umber black, violet black. Eventually they just shimmered.”

The effect is uncanny: a storm of marks that seems to hurtle through the air in front of the picture itself. Behind it, a gray mist plays peek-a-boo with fine-line renderings of windows, pediments, and facades—a city in freefall. There is no position from which all three zones can be read at the same time. Step back and you lose the city; step forward and you miss the cloud. For Mehretu, Epigraph, Damascus was pivotal: “a moment of being able to play with the blur and the drawing and the more haunted images I was trying to create, which only came later in painting.”

In the paintings that followed, the blur took on chromatic range and mutability. So, for their second project, Niels had the idea of breaking the blurred photo onto two photogravure plates—filtering one for hot colours, the other for cool. The two would be related, but with different weights in different areas. As always, the plates could be inked in any hue. Sized to accommodate a full body gesture (almost two metres in width), each of the new prints would require four sheets of paper, printed separately and then joined. Blurred news photos of immigration confrontations in two hemispheres were separated into two layers, and printed in red and blue at the size of the planned prints. Mehretu again drew over the proofs with brushes, ink wash, and airbrush, using different mylars for marks in different colours. Finally, in late 2019, she went to Copenhagen to complete the copper plates for the first of four planned prints. The remainder were to be done in the spring.

Then COVID paused the world. Loath to lose momentum, they decided to finish the prints remotely. The twelve remaining copper plates (four for each of the unfinished prints) were shipped to the artist in New York. They also sent Niels’s sugar lift solution, which had never encountered an American summer. At her studio in rural New York, Mehretu found the lift wouldn’t stick to the plates.

“Niels had to walk me through mixing degreasers from supplies I could find in the Catskills. The next problem was that I would finish a plate and let the sugar lift dry, but when we went to pack it up the next morning it would be completely tacky again. The sugar just absorbed all the humidity from the air. We had to figure out a way to dry them with heaters and then seal immediately so moisture couldn’t get in. Then, we just had to pray.”

When, at last, the plates arrived back in Copenhagen, the proofing had to be conducted remotely. Each of the thirty-six gravure plates and sixteen copper plates were to be inked in multiple colours, à la poupée. The number of potential variables was incalculable. Zoom meetings were held every couple of days through the summer and fall.

“They were incredible. If I explained that there was a section that I wanted to feel “more like light” or a colour that I wanted to be “more intense, but not intense in a way that feels heavy, that feels like light rather than pigment,” they could materialize that, not just in the plate but in the way they mix the inks and the way they wipe the ink. Their hands just whisper over the plate. Toward the end, the prints had presence but weren’t quite there. Then suddenly—they felt illuminated from inside. The ink feels immaterial. The way the printers work is like this beautiful dance. They go into this meditative place where they do their thing and out comes … magic. They’re like wizards.”

The wizards calculate it will take three full-time printers more than a year to complete the edition. In the meantime, Slouching Towards Bethlehem made its New York debut the day before the American election in November 2020, as part of Mehretu’s exhibition “about the space of half an hour” at Marian Goodman Gallery. The time frame is that given in the Book of Revelation as the hiatus between the opening of the Seventh Seal and the Second Coming.2 Like the prints, it frames “this moment of pause, a threshold, a space in between.”

Susan Tallman

No Plan at All, Hatje Cantz 2021

2 In the Christian bible, the Book of Revelation describes the Second Coming of Christ, which is preceded by the opening of seven seals, and brings about the Apocalypse. Each of the prints in Slouching Towards Bethlehem is named for one of the seals and subtitled with the number of the relevant chapter and verse.

About Julie Mehretu

One of the most recognized visual artists of our time, Mehretu creates works that are direct responses to urgent political matters such as the rise of fascism, undemocratic futures, colonialism, mass migration, displacement, and social protest. She combines manipulated digital images with her distinct painterly vocabulary of organic, painterly marks. Her multi-layered, large-scale compositions can be seen as visual explorations of our collective struggle to comprehend the social and political complexities of a globalized, chaotic, fragmented world.

Selected solo exhibitions include The Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, 2021), LACMA (Los Angeles, 2019/20), The High Museum (Atlanta, 2020), The Walker Museum of Art (Minneapolis, 2021/22). Mehretu has participated in the Biennals of Venice, Istanbul, São Paolo, and Sydney, as well as in Documenta XIII.

Julie Mehretu was born in 1970 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and lives and works in New York City. She has been collaborating with BORCH Editions since 2015.

Learn more about Julie Mehretu