In his work, Al Taylor gave objects and ordinary routines a life of their own through his innovative and humorous approach to investigating and envisioning the world and what it could be.

Al Taylor

Inquire

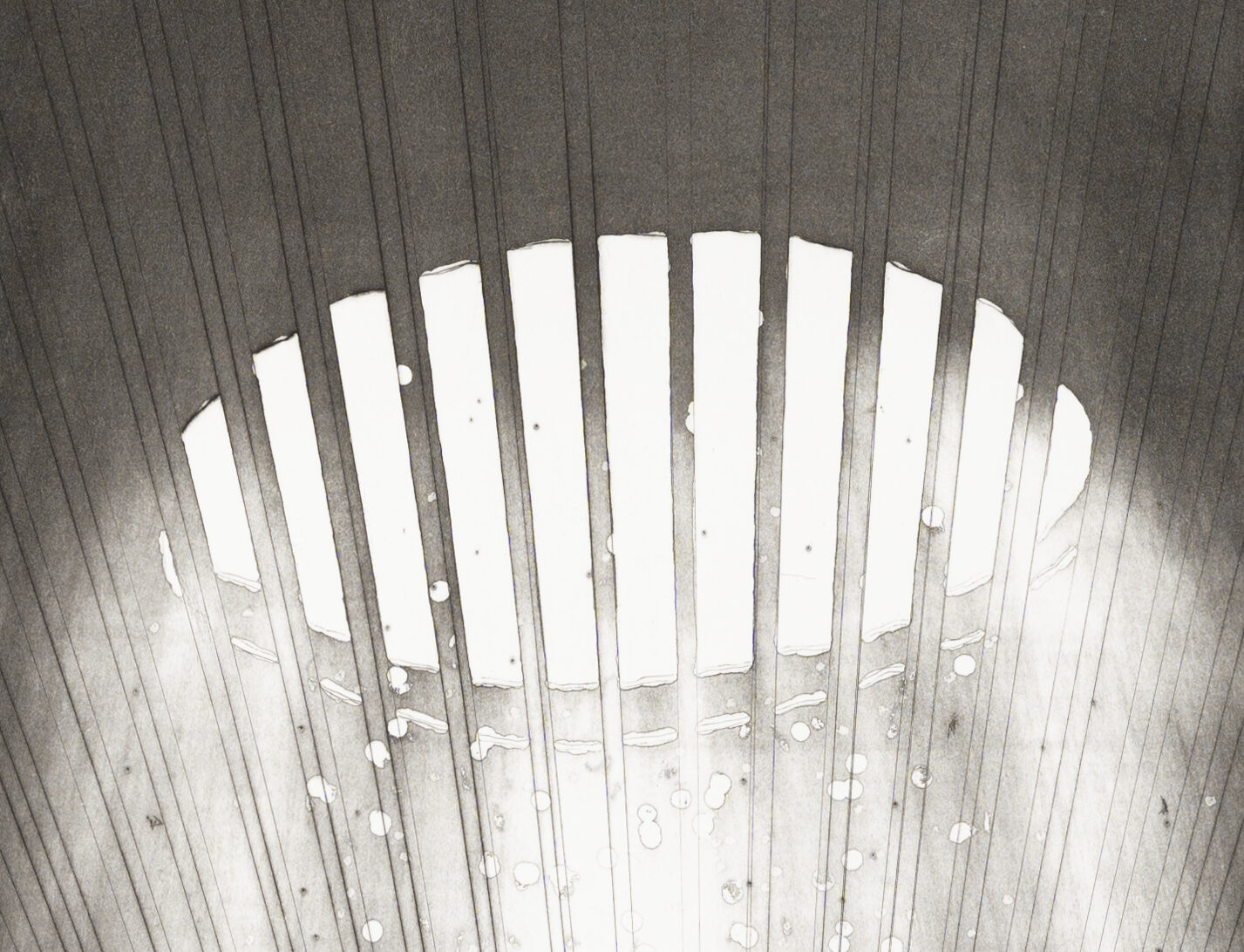

Ventilated Ceiling, from the series Ten Common (Hawaiian Household) Objects, 1989

Look, what I am asking the pieces to do is to make themselves somehow. Instead of forcing myself onto some anonymous objects, I try to find a method that will allow them to find their own logic beyond me

Al Taylor

In his work, Al Taylor gave objects and ordinary routines a life of their own through his innovative and humorous approach to investigating and envisioning the world and what it could be. His artistic practice is one heavily informed by observation and experimentation – he often seeks to push the boundaries of logic and reimagine the experience of space and daily routines.

As a multidisciplinary artist, Taylor worked in multiple mediums, including drawing painting and sculpture. Across mediums, the motifs of perception, dimension, and spatial exploration remain constant. Even in his two-dimensional works, depth and the exploration of space are critical elements of his art.

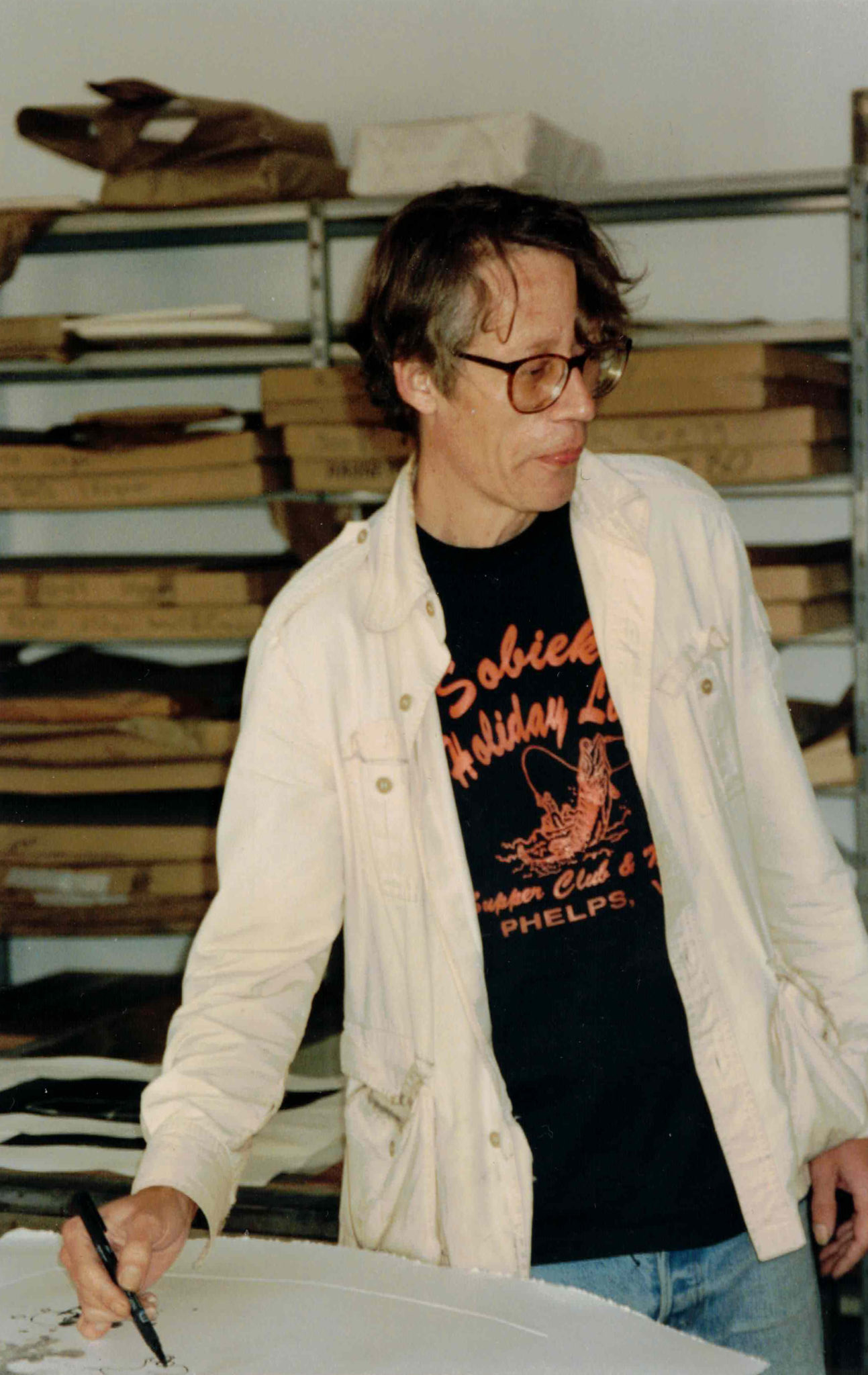

While visiting an art dealer in Cologne, Niels Borch Jensen was introduced to Al Taylor, an artist he had never heard of or seen work by before. Taylor’s relationship with Niels Borch Jensen and BORCH Editions began by chance and blossomed into a prosperous working relationship and friendship. After their fortuitous meeting, Jensen invited Taylor to Copenhagen to make some prints; over a year later, he finally made the trip from New York to Copenhagen. Jensen describes working with Taylor as a challenge in regards to figuring out how to create the desired effects, which aren’t too common in printmaking.

Their mutual interest in and love for experimentation pushed them to act as both scientists and artists; during this time, they played around with spitbite, etching, drypoint, and other techniques and combined multiple methods to try and yield the desired effects.

Al Taylor, who is often described as a sculptor but always thought of himself as a painter, was “one of those extraordinary people who pays attention to things you don’t think about and finds something quite beautiful,” in the words of curator David Kiehl. If Paul Klee famously likened drawing to “taking a line out for a walk,” and David Hockney was described as taking a line for a walk and a talk, Taylor might be seen as taking a line out for a drink in the kind of dive bar that becomes lovelier with each downed shot.1 He could work anywhere, because there were things to see everywhere. One of the first prints he made with Niels portrays an unfurled length of flypaper, dangling dark and disconsolate, ignored by myriad midges. It has the damp beauty of a silhouette in fog, the tawdry optimism of a party streamer, and the comic precision of a pratfall. Small wonder he and Niels hit it off from the start. Flypaper is one of Ten Common (Hawaiian Household) Objects, a 1989 portfolio whose other subjects include window screens, water bottles, and something called “sex rocks.” Having seen simple sketches that the artist made in Maui and Kauai, his Cologne gallerist, Alfred Kren, thought they might lend themselves to etching. Niels agreed. Taylor, however, had no desire to replicate extant drawings. He had been making prints since art school and had just completed several etchings with the esteemed New York printers Felix Harlan and Carol Weaver. Copenhagen represented an opportunity to investigate known subjects through new materials and strategies. “Before he came,” Niels recalls, “he sent a list of commonplace Hawaiian objects—mosquito coils, coconuts, thongs—for me to purchase. In Denmark. In November. Which does not have a Hawaiian climate.” It took some hunting, but they secured most of them.

1 The Hockney line comes from Marco Livingston,

David Hockney Etchings and Lithographs

(Thames & Hudson, London, 1988)

Unprepossessing visual events are distilled, like homeopathic medicine, into traces of the quirks that drew his eye. A broom is reduced to a handle, the handle to a loop of line, and the line is repeated dozens of times to capture its habit of leaning again and again in more or less the same place. The wall smudges were reenacted by painting acid on the plate and swiftly wiping it off, roughening the spot just enough to hold a bare scrim of pigment. Lodging in the printshop’s guest room, he would work all night on plates.

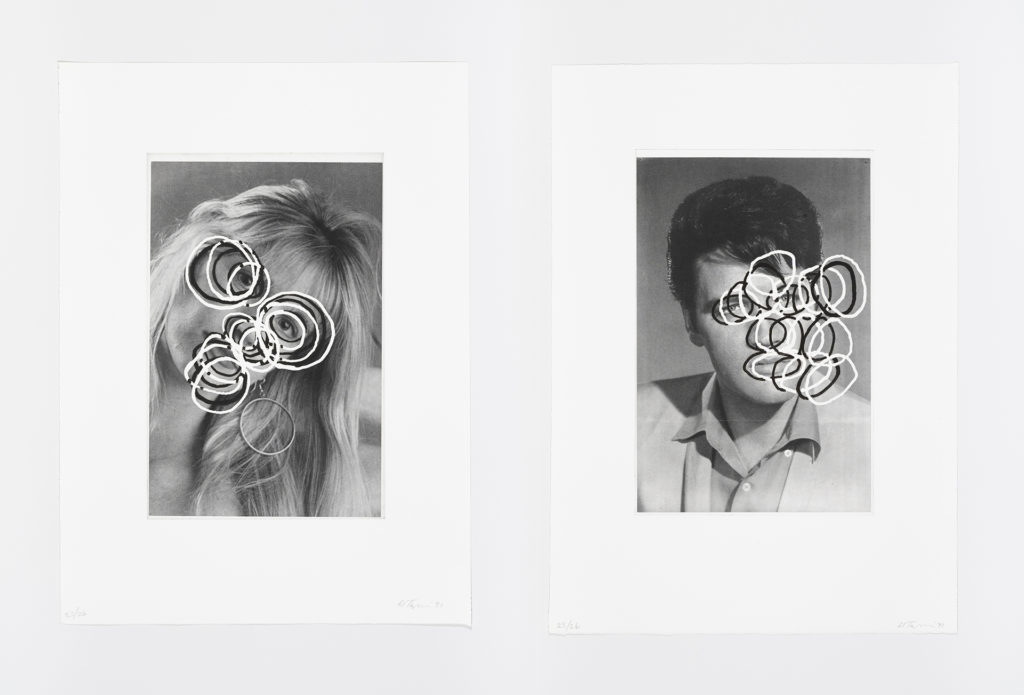

When he returned in 1991, Niels’s photogravure experiments were just coming to fruition. In New York, Taylor had been making a series of drawings titled Face-Off, in which he applied black gouache and white correction fluid to faces clipped from magazines and newspapers, extending the eyes, noses, and mouths with spring-like circles. Both artist and printer were curious to see how gravure’s heavenly grays would knock against the brilliant whites and stygian blacks of intaglio. The perfect subject was, typically, found near at hand: “Anneli had just held a birthday party in the printshop,” Niels recalls, “and a friend had wrapped her gift in Elvis posters. One was pinned to the wall in the printshop, where Al saw it.” They embalmed Elvis in photogravure, then festooned him with rings of black and white radiating from his eyes, nose, and mouth— a loopy expansion of the X-Ray Specs once advertised in the backs of comic books. To fend off any hint of Warhol-like celebrity salutation, Taylor thought Elvis should have a partner—not his actual wife, Niels explains, but “someone who looks displaced, like she’s wondering ‘what am I doing here?’” The garage downstairs refused to lend its Pirelli calendar of half-naked models lounging on tires, but in Copenhagen, Taylor found a biker magazine with snapshots sent in by readers. Amid the leather-clad guys showing off their hogs and girlfriends, he found a deadpan blonde with big hoop earrings that neatly matched the black and white circles she soon acquired. Mr. & Mrs. was the printshop’s first photogravure edition.

One of the things Niels liked about American print culture was its consideration of the print as an object, rather than just an image that happened to sit on a sheet of paper. Margins were often calculated as part of the composition, and signatures often sat at the bottom of the sheet rather than just under the plate mark. Taylor was keenly alert to such aspects: in the print of Elvis, the image is positioned unevenly on its plate, leaving an area of white at the top to deliver the almost subliminal suggestion of a neglected family photo that has slipped in its frame. “Al always had a surprising angle on what was important, where he was looking. You could spend hours in a bar, just noticing interesting bits. He had a very European sensibility, but a very American way of giving importance to every part.”

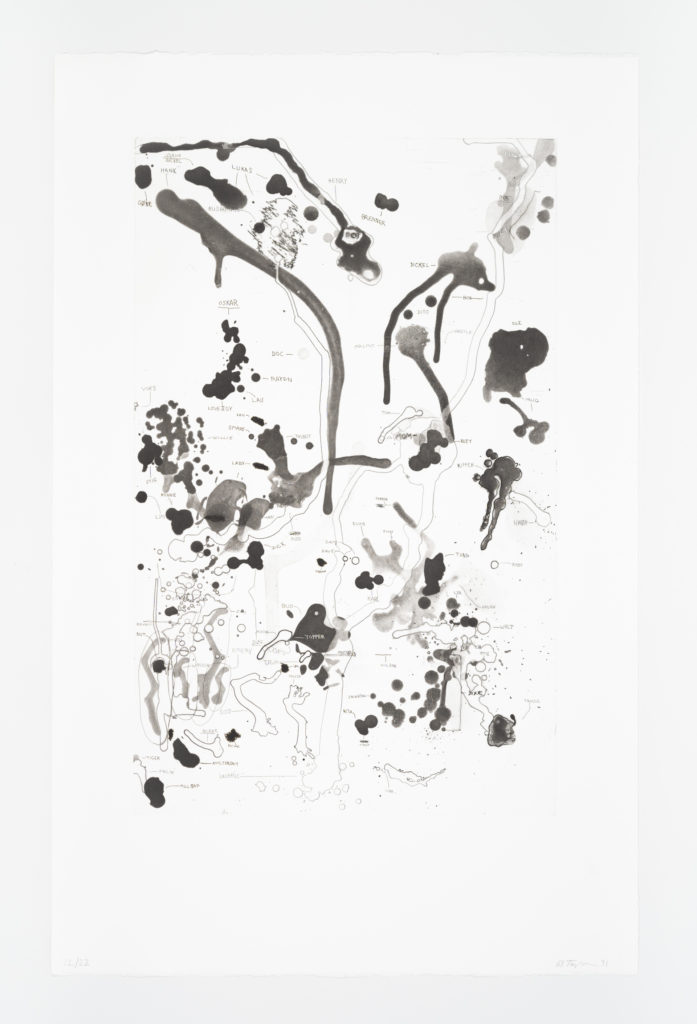

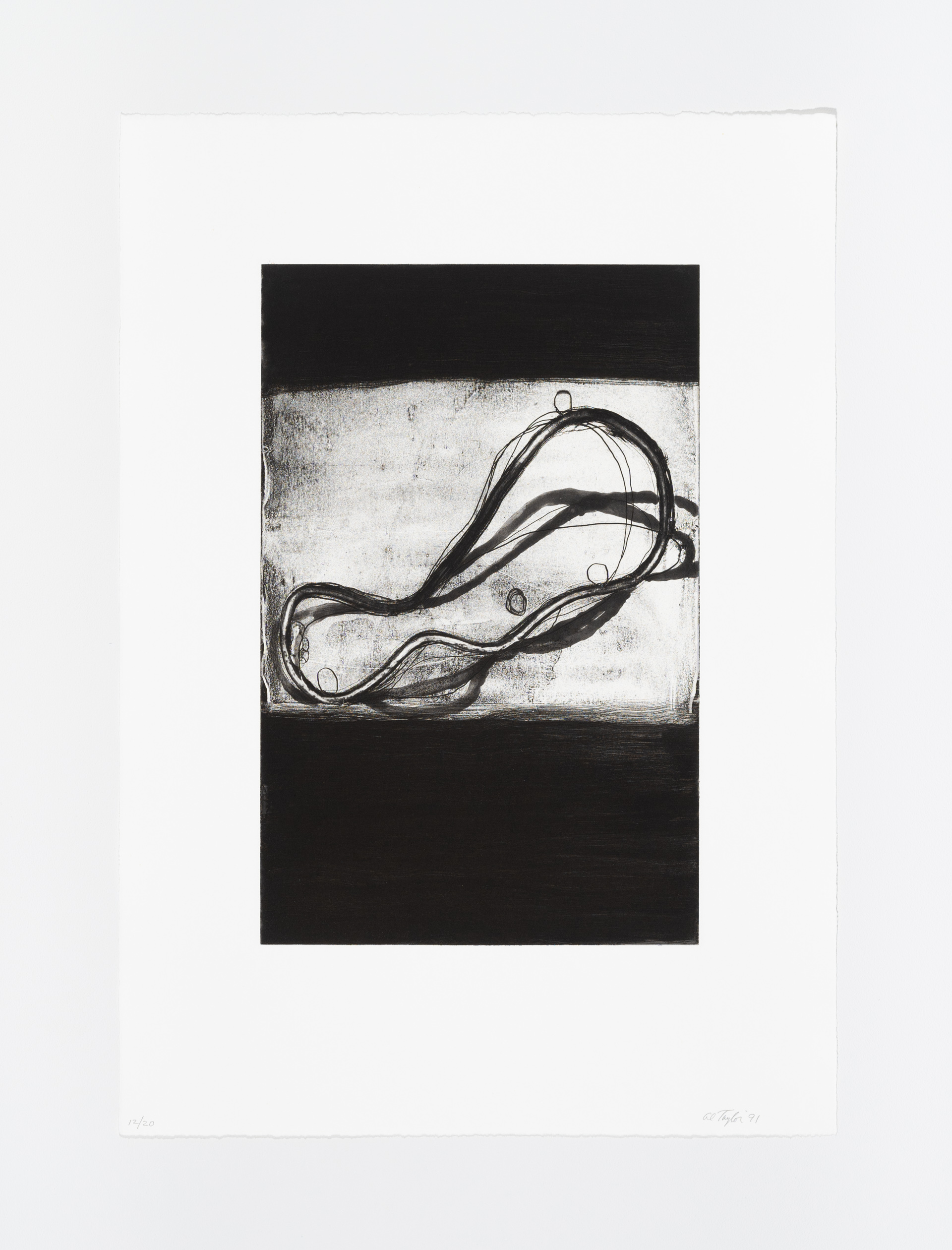

Over the course of a week, Taylor completed fifteen other editions and began thirteen more. (In addition to humour and drinking habits, he and Niels were well matched in their prodigious appetite for work). In Pass the Peas, (1991), he spun variations on meandering wires, tubes, and small rolling circles; in the peculiar Hanging Puddles, (1991), flaccid ovals drape over wires rigged like laundry lines. The liquidly lyrical Pet Stains, (1991) arose from his observations of Parisian dogs marking their territory on a street corner in Montmartre and the unpredictable trajectories that resulted. To make the prints, he dribbled spit bite of different thicknesses and strengths onto the plates and tilted them in different directions. “Al quite liked that sense of not being fully in control. He liked the game of it—you try stuff out, you see what you get, and you react to that. That is often the mark of people who are passionate printmakers.” Any pretensions to the legacy of high-art dribblers like Jackson Pollock are dispatched by the dog names scratched beside each stain—Casper, Howard, Imelda, etc.—a kind of canine Marauder’s Map. Sarah Suzuki first saw Pet Stains when she was cataloguing the Museum of Modern Art’s print collection:

I was going through 60,000 prints, but it made me stop and ask, what is this? I did not know who Al Taylor was and I did not know who Niels was. But here was this sense of both beauty and irreverence. They had taken these finicky etching mediums and just said “let’s play with it.” It was something I had not seen in print before.

Together, Taylor and Niels had “amassed a virtually unlimited range of possibilities for experimentation in the etching medium,” according to curator Michael Semff.2 “They had so much in common,” his wife Debbie notes:

Their sense of humour, their mischievousness, their willingness to take chances, and wanting to know more, to learn more, in life. You would almost think they were brothers. When we were in New York, they spoke on the phone every week or so. Niels was publishing all those prints, and he could maybe sell six of them. There was no Al Taylor market at that time. But Niels was in it for the same reasons Al was — to go further, to expand possibilities.

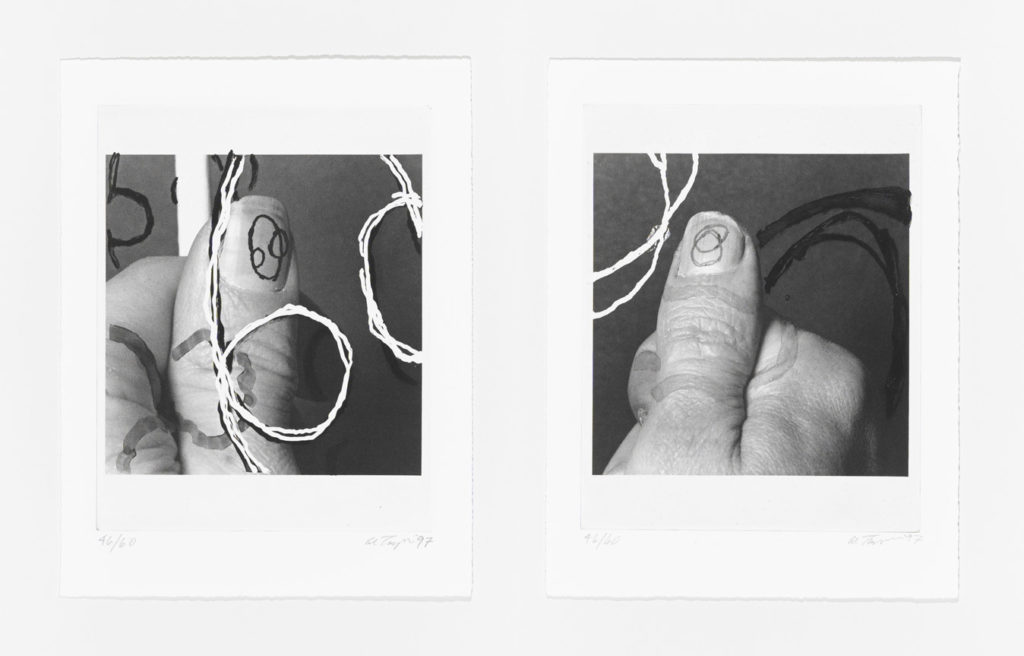

In 1997, when Niels was teaching at the art academy in Malmö, he arranged for Taylor to come over as a guest artist. For his photogravure series done there, Taylor first drew small doodles on his thumbnails in photos, then scanned them, then redrew the same motifs on plates as if they were things in real space lying over and under the digits, sometimes straying out of the photograph and into the margins—sly allusions to the presence of the “artist’s hand” in the hands of an artist whose curiosity was always trained on the wonder and weirdness of the world. The plan was for Taylor to return in the not-too-distant future to finish half-completed projects and embark on new adventures. In December 1998, however, he was diagnosed with lung cancer. When Niels and Anneli flew over to see him, he was in hospital, plotting how his chest X-rays might be used in future prints. He died on March 31, having just turned fifty-one. The catalogue raisonné of Taylor’s prints, shows how critical printmaking was to the artist. The book quotes Taylor speaking about his drive to create “elaborate programs, systems, and methods which break down, fall apart, and change the more successful they become, taking on meanings and a life beyond.”3 It also quotes Niels, speaking about Taylor: “For me, printmaking is always a matter of curiosity. I love the moment when I see something and I don’t get it, but I know it’s something good, and with Al that happened a lot.”4

Susan Tallman

No Plan at All, Hatje Cantz 2021

2 Michael Semff, et al. Al Taylor Prints: Catalogue Raisonné (Ostfeldern, 2013), p. 27.

3 Al Taylor in Semff, et al. Al Taylor Prints: Catalogue Raisonné (Ostfeldern, 2013), p. 7.

4 Niels Borch Jensen in ibid., p. 263.

About Al Taylor

Al Taylor’s first solo exhibition took place in 1986 at the Alfred Kren Gallery in New York. His work would go on to be shown in numerous exhibitions in America and Europe, including solo exhibitions at the Kunsthalle Bern (1992) and the Kunstmuseum Luzern (1999), both in Switzerland.

A retrospective of Taylor’s drawings was organized posthumously by the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung at the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, in 2006. A retrospective of the artist’s prints opened at the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, in September 2010, and traveled to the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark, in Spring 2011. The Santa Monica Museum of Art, California, presented a focused overview of two bodies of work by the artist, Wire Instruments and Pet Stain Removal Devices, in 2011. In 2013, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta mounted the exhibition Drawing Instruments: Al Taylor’s Bat Parts and Endcuts. In 2014, The Philip Johnson Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, presented Six Panels: Al Taylor, curated by Robert Storr. A major survey of the artist’s work was presented at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta in 2017-2018. The Drawings of Al Taylor was on view at The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, in 2020.

Work by the artist is represented in a number of prominent public collections, including the British Museum, London; Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland; High Museum of Art, Atlanta; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, among others.

Al Taylor was born in Springfield, Missouri in 1948 and moved to New York in 1970, where he would continue to live and work until his death, in 1999. He collaborated with BORCH Editions from 1989 until 1998.

Learn more about Al Taylor